Developing a Modern Search Stack: NER & More Precise Search Results

Authors

Date Published

Share this post

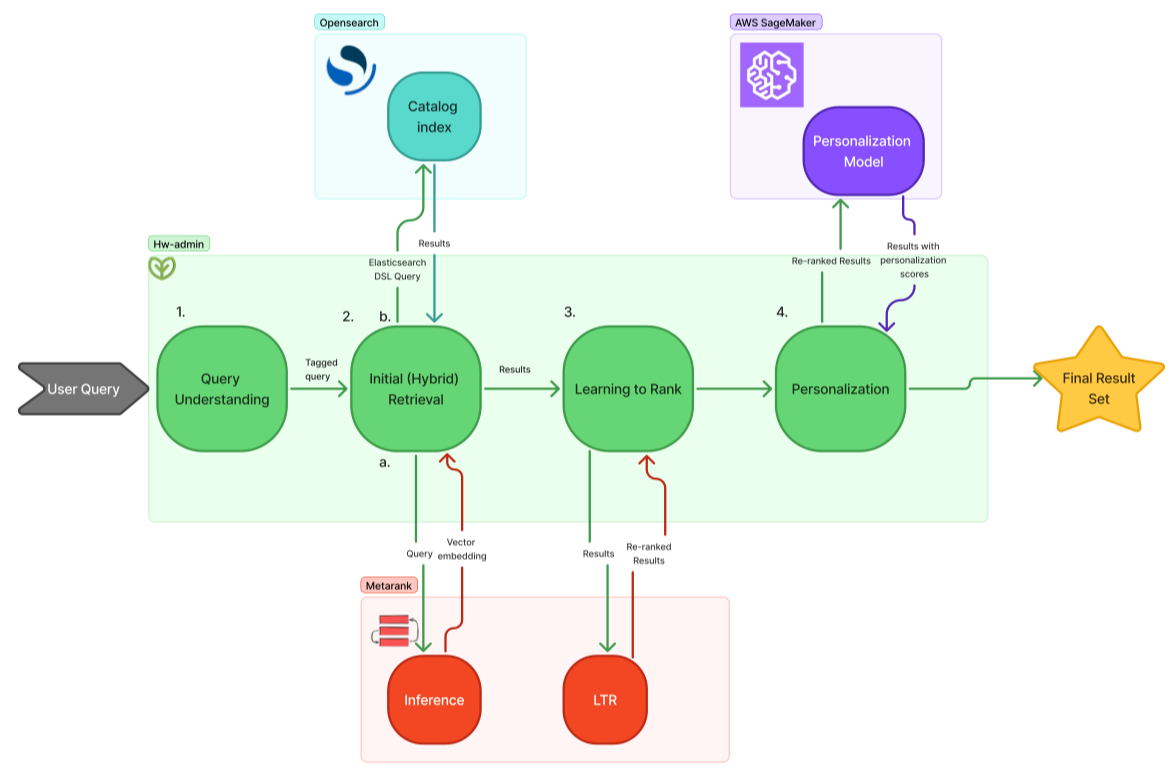

This article is part of a series from Fullscript about how we built our modern search stack. You can find the other articles here.

In part 3 of this blog series, we explained how we used Metarank to help us build a learn-to-rank (LTR) service that increased the relevancy of our search results. Despite these gains, we still had the issue of irrelevant products being returned to our users. This problem mainly occurred when users searched with multiple entities in their query. For example, a user could search with multiple ingredients (“vitamin c” and “iron”) or a brand and an ingredient (“Thorne” and “magnesium”). Given that our Elasticsearch query used “OR” logic to return products from our index, any product that matched with either entity was returned. So for the query “Thorne magnesium”, all products from Thorne and all products with magnesium were returned. Often, our reranking service could compensate for this and put the magnesium products from Thorne at the top of the results, but the ranking wasn’t always ideal, and many irrelevant products were being returned (e.g. non-magnesium Thorne products and non-Thorne magnesium products). To address this issue, we built an NER service.

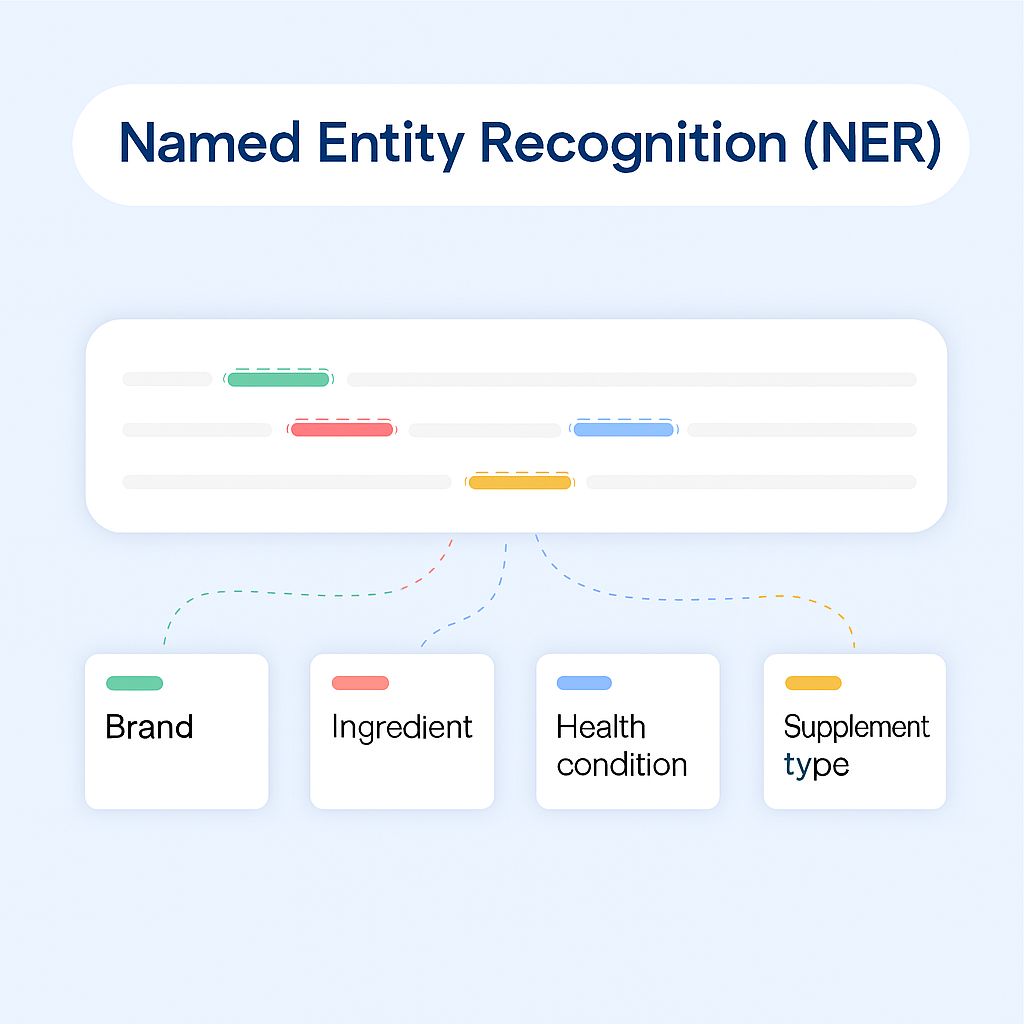

Named-Entity Recognition (NER)

An NER service recognizes entities (i.e. categories or words) in text. We built our service to identify ingredients, brands, health conditions, supplement types, and a few other entities. By knowing which words in a user’s query correspond to an entity, we could dynamically create our Elasticsearch query. For example, before our NER service, the Elasticsearch query for “Thorne magnesium” would look like:

1{2 "query": {3 "bool": {4 "should": [5 { "match": { "name": { "query": "throne magnesium", "boost": 2.5 } } },6 { "match": { "name.keyword": { "query": "throne magnesium", "boost": 4 } } },7 { "match": { "description": { "query": "throne magnesium", "boost": 2 } } },8 { "match": { "ingredients": { "query": "throne magnesium", "boost": 1.5 } } },9 { "match": { "brand": { "query": "throne magnesium", "boost": 1 } } },10 { "match": { "brand.keyword": { "query": "throne magnesium", "boost": 3 } } }11 ]12 }13 }14}

And after implementing the NER service, the Elasticsearch query would look like:

1{2 "query": {3 "bool": {4 "must": [5 { "bool": {6 "should": [7 { "match": { "ingredients": { "query": "magnesium", "boost": 1.5 } } }8 ]9 }10 },11 {12 "bool": {13 "should": [14 { "match": { "brand": { "query": "throne", "boost": 1 } } },15 { "match": { "brand.keyword": { "query": "throne", "boost": 3 } } }16 ]17 }18 }19 ]20 }21 }22}

Now we have a nested query where each clause must have one matching field for a product to be returned. In some cases, this resulted in a huge decrease in the number of search results, e.g. from 1000s to <10. Our users were delighted when they saw these much more precise search results.

Building the NER Service

Our NER service runs with every user query, so it needs to be fast. To save time, we chose to include the new service in our monolith rather than create a microservice. This limited the memory that we could use (e.g. no deep neural networks), but our users’ queries are often short (1-3 words) and spelled correctly, so we didn’t expect the service’s accuracy to be overly harmed by this decision.

The first version of the NER service was quite simple. It did not account for any spelling mistakes (so no fuzzy matching), and all tokens (i.e. words or numbers) must match to an entity in our database for the NER service to update the Elasticsearch query. The service was largely (1) an index mapping tokens to entities and (2) some matching logic. The entity index looked like this:

1{2 “magnesium”: “ingredient”,3 “vitamin c”: “ingredient”,4 “thorne”: “brand”,5 “pure encapsulations”: “brand”,6 “probiotics”: “supplement_type”,7 …8}

The matching logic worked by iteratively parsing a user’s query. For example, the query “iron oxide pure encapsulations liquid” is searched in the following chunks:

iron oxide pure encapsulations liquid - start by attempting to match the entire query (no match)

iron oxide pure encapsulations - the final word is removed (no match)

iron oxide pure - again, remove the final word (no match)

iron oxide - a match is made! Remove these tokens from the matching process

pure encapsulation liquid - attempt to match with the entire string, except for what has already matched (no match)

pure encapsulation - a match is made! Remove these tokens from the matching process

liquid - a match is made! Since all tokens have matched, we can stop the process

This version of the service was quickly followed by an update that included fuzzy matching.

NER v2

Fuzzy matching introduces some complexities. Since it’s not feasible to compare the spelling of one token with all tokens in your entity index, you need a way to determine which tokens are worth comparing. There are a few different approaches that include:

- Convert tokens to vectors, measure cosine similarity, and return the top N.

- Convert tokens to an encoding (e.g. NYSIIS, Soundex, Metaphone), and return all that match the input token’s encoding.

- Build a tree that accounts for typos (such as using DFA), and return the tokens within the typo-tolerant range.

We chose the encoding approach as it balanced predictability, accuracy, and speed. Our encoding is a variation of NYSIIS. We made a few changes to the logic to better suit our vocabulary. By encoding all of our tokens using this method, we could quickly find a set of similar tokens to fuzzy match. The encoding index looks like this:

1{2 “ABCPRT”: [“prebiotics”, “probiotics”, ...],3 “ANPRT”: [“pea protein”, “protein”, ...],4 “ANTV”: [“vitamin”, “vitamin a”, ...],5 …6}

Once you have a set of candidate matches for a token (e.g. “probiotc”), the next challenge is determining which one, if any, is a match. We developed a matching algorithm using phonetic and spelling features to measure the similarity between the candidates and the input token. Given that our encoding method can produce a large number of candidates, our similarity algorithm was designed to be very fast, <1ms per comparison, and has an early stop if a very high-quality match is found.

Using this two-step process of (1) finding candidate matches and (2) selecting the best candidate as a match allowed our NER service to be lightweight, fast, and accurate. Our search results are much more precise and our users can find the products they are looking for more easily.

Share this post

Related Posts

Developing a Modern Search Stack: An Overview

An overview of how Fullscript built a modern search stack to provide more relevant results to its users.

Developing a Modern Search Stack: Learning-to-Rank with Metarank

How we used Metarank to quickly build a learning to rank service to improve the NDCG of our search engine.